Daydream is an important entry in the long (and ongoing) history of the Pinku eiga. The first of its kind to be released in mainstream cinemas (which sort of means it doesn’t count as a Pinku film), Daydream is one of the few Pinku films to circulate outside of Japan. While most Pinku films (and even higher budgeted Roman Porno and Pinky Violence films) are left to rot in obscurity, Daydream received two theatrical releases in the United States (its second release containing extra colour scenes shot by none other than Joseph Green) and was screened at the Venice Film Festival. It’s also one of the few Pinku films to receive a DVD release with a nice looking transfer (as far as I know, its only available in Japan – please correct me if I’m wrong), which has allowed me to finally see it. While articles and books have led me to believe that the film may not be quite as shocking or as impressive as it was back in 1964, Daydream left me thoroughly satisfied and more than a little bemused.

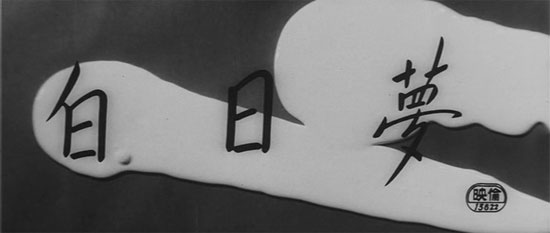

DAYDREAM

original title: Hakujitsumu (白日夢)

1964, Tetsuji Takechi

I don’t want to spend long discussing Daydream‘s plot. Despite its literary source, the film’s story is largely irrelevant. We open with a man, Kurahashi (Akira Ishihama), and a woman, Cheiko (Kanako Michi), in a dentist’s waiting room. Kurahashi is clearly entranced by Cheiko, but says nothing to her. The dentist (Chojuro Hanakawa) calls in Kurahashi and Cheiko to the examining room. They sit side by side as the dentist checks their teeth in what is probably the oddest scene of dentistry put to film. Kurahashi is given an anesthetic. As he falls asleep, he watches/imagines Cheiko, also unconscious, being bitten and abused by the dentist. The film then slips into a series of dreams as Kurahashi pursues Cheiko. In his dreams, Cheiko is continually abused and dominated by the dentist who claims that he owns her. Kurahashi attempts to rescue her from her complicated and degrading relationship.

I don’t want to spend long discussing Daydream‘s plot. Despite its literary source, the film’s story is largely irrelevant. We open with a man, Kurahashi (Akira Ishihama), and a woman, Cheiko (Kanako Michi), in a dentist’s waiting room. Kurahashi is clearly entranced by Cheiko, but says nothing to her. The dentist (Chojuro Hanakawa) calls in Kurahashi and Cheiko to the examining room. They sit side by side as the dentist checks their teeth in what is probably the oddest scene of dentistry put to film. Kurahashi is given an anesthetic. As he falls asleep, he watches/imagines Cheiko, also unconscious, being bitten and abused by the dentist. The film then slips into a series of dreams as Kurahashi pursues Cheiko. In his dreams, Cheiko is continually abused and dominated by the dentist who claims that he owns her. Kurahashi attempts to rescue her from her complicated and degrading relationship.

Kurahashi watches helplessly as Cheiko is tortured

Daydream is a fascinating time capsule. For better or worse, it is undoubtedly an independent film of the 60s. And that may turn some viewers off. Its eroticism and horror is wrapped in a specific experimental style could not exist in any other decade. This may lead some to dismiss Daydream as dated and hammy. And, admittedly, its predictable (and most certainly hammy) ending does strip the film of some of its power. But it’s hard to ignore the film’s stylistic approach – an approach, while reeking of 1964, I found wholly unique. Daydream excels in its presentation of dream logic and, although its narrative may be irrelevant, Tetsuji Takechi’s dissection of his characters’ desires, perversions and masochistic and sadistic leanings is fairly complex. On a purely physical level, Daydream is chilling. There are scenes here that truly put me on edge.

Takechi even manages to make a monkey appear terrifying

Daydream blends its visuals with audio perfectly, and its sound design is possibly its strongest asset. The film’s opening in the dentist’s office fills the speakers with intrusive sounds of whirring drills, slurping and spraying. The moaning of the dentist’s patients is layered over the top creating an uncomfortable sexual parallel. This whirring and slurping does not stop when we leave the dentist’s office. These sounds are beautifully appropriated into the film’s score. It’s difficult to pinpoint where Daydream‘s sound design ends and its musical score begins. Essentially, they are one in the same. The music used in Daydream is wonderful. At times, it is minimalistic, other times it is (appropriately) overbearing.

The dentist

Equal to the stunning sounds of Daydream is the cinematography. While the film may be free from subtlety, the imagery remains powerful. Despite a low budget, every shot is framed with the utmost of care. There is little dialogue in Daydream and its story and character relationships are mostly explained through camerawork. I’d go as far to say this film would make perfect sense – or at least the same amount of sense – without the English subtitles. Some scenes are so powerful in their visuals, they are actually nauseating. There is a scene where Kurahashi searches for Cheiko in a strangely designed children’s playground. He watches a chained monkey lurking amongst the playground equipment. The scene cuts between shots of Kurahashi and his point of view. His point of view is shot in a dizzying wide-angle shot that somehow made me feel faint. The confronting and unsettling comparison of a chained monkey and a chained Cheiko did not help my state of mind. Many Pinku films of this era have one scene shot in colour (a budgetary issue that, for some, morphed into an artistic expression), and Daydream is no exception. Daydream‘s colour sequence acts as a dream within a dream, and it is shot in a way to distort its audience’s perception. I’m not sure how this scene plays out of the context of the film, but here it is:

Part of me wants to say that I couldn’t recommend Daydream more, but I know that it won’t win over everyone. It wears its style on its sleeve and I suppose you could say it is lacking in substance. (I personally wouldn’t say that.) Some may only want to see it as a curiosity item – it is definitely an important part of Japanese cinema history and of erotic cinema history – only to swiftly discard it from their memory banks. I doubt many would watch this as pornography; the notion of an erotic nightmare is not exactly a universally appealing concept, and I can’t imagine anyone managing to fap to this (unless, of course, you have a fetish for dentistry). Daydream is a film that most cinematic scholars would scoff at, and a less patient modern audience would switch it off after a few minutes of obnoxious whirring sounds. But for those of you (or should I say, “us”) that like this sort of thing – whatever “this sort of thing is” – yes, I couldn’t recommend Daydream more!