Some weeks ago, I discussed Serial Rapist (1978) in a Nihon Nihilism post. The man behind that harshly titled nastiness was Kôji Wakamatsu. For this post, I’ve chosen to look at one of Wakamatsu’s earlier works. I’m not well-versed in his films, but from what I’ve read – and from what little I’ve seen – his films of the late 70s have a much harder edge. His work of the 60s – for better or worse – leans towards poetic exploitation with stark black and white photography often set against the words of legendary screenwriter, Masao Adachi. One of the better known collaborations between Wakamatsu and Adachi is The Embryo Hunts in Secret…

Some weeks ago, I discussed Serial Rapist (1978) in a Nihon Nihilism post. The man behind that harshly titled nastiness was Kôji Wakamatsu. For this post, I’ve chosen to look at one of Wakamatsu’s earlier works. I’m not well-versed in his films, but from what I’ve read – and from what little I’ve seen – his films of the late 70s have a much harder edge. His work of the 60s – for better or worse – leans towards poetic exploitation with stark black and white photography often set against the words of legendary screenwriter, Masao Adachi. One of the better known collaborations between Wakamatsu and Adachi is The Embryo Hunts in Secret…

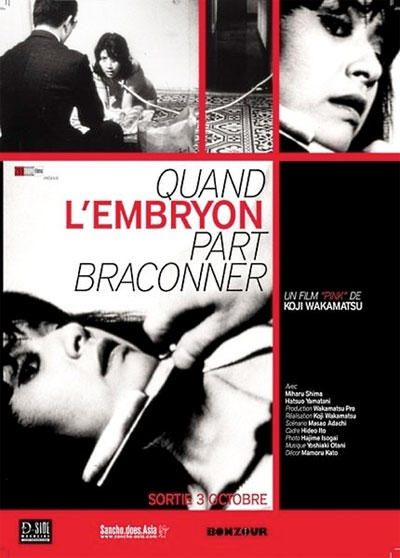

THE EMBRYO HUNTS IN SECRET

original title: Taiji ga Mitsuryō Suru Toki (胎児が密猟する時)

1966, Kôji Wakamatsu

"Why did I not die in the womb?"

I won’t lie, The Embryo Hunts in Secret didn’t exactly blow me away. But it left an interesting aftertaste. And as a piece of Japanese cinematic history, it’s fascinating. Playing out as a sleazy arthouse film, The Embryo Hunts in Secret plants stylistic and thematic seeds – seeds that have bloomed into the grit and sleaze of modern Japanese exploitation. The film, like many that appear in Nihon Nihilism, is intensely depressing. It becomes apparent that the lead character’s madness goes beyond twisted sexual gratification. Instead, it comes from a misanthropic world view – a view that ties itself to the film’s odd title. The antagonist – if you can call him an antagonist – attempts to turn his captive into an animal, a dog to be precise, something that he has mixed success with. The pleasure that he takes in implementing this transformation is disturbing indeed.

Training

Both Wakamatsu’s direction and Adachi’s writing lack subtlety, but it’s hard to deny their strengths as filmmakers. Wakamatsu works wonders with a nonexistent budget. Apparently The Embryo Hunts in Secret was shot almost entirely in Wakamatsu’s office. Wakamatsu cleverly hides this with cinematography that’s almost awe-inspiring. The lighting often demonstrates the mental states of characters, rather than adhering to reality – it fades in and out, sometimes hiding characters in shadows and other times washing them out with light. The camerawork is equally dynamic, especially when you compare this to the bulk of independent exploitation coming out of the Western world in the 60s. Adachi’s dialogue is relentless and repetitive. It is almost always far too obvious in its intentions. But Adachi plays with some very brave and dark concepts.

The beginnings of Japanese sleaze

The Embryo Hunts in Secret is not quite the masterpiece of exploitation that some make it out to be, but it is a strangely hypnotic film. The film becomes more interesting after reading about its filmmakers and its place in Japanese cinema history. While it may be flawed and somewhat pretentious, The Embryo Hunts in Secret, I suppose, could be called groundbreaking. Most will dismiss this as dated garbage, but those of us hooked on Japan’s darker offerings will find The Embryo Hunts in Secret very revealing.

3 comments

An interview with Jasper Sharp | MONDO EXPLOITO says:

Oct 1, 2012

[…] fascinating were those on Kōji Wakamatsu and Masao Adachi. I knew of these two from films like The Embryo Hunts in Secret, but I knew little about their political leanings and their run-ins with the law. Were you able to […]

Violated Angels (1967) | MONDO EXPLOITO says:

Aug 30, 2013

[…] Angels takes a similar approach to Wakamatsu’s The Embryo Hunts in Secret, shot the previous year. Both take place almost entirely in a single location, and both are […]

Abortion (1966) | MONDO EXPLOITO says:

Jun 4, 2015

[…] Adachi served as a writer — for example, the brilliant Violated Angels (1967) and claustrophobic The Embryo Hunts in Secret (1966) — he also directed a handful of his own scripts. Alongside films like the experimental […]