It was love at first sight. Oh Hausu (1977) – what a film! Not often do I feel that a film has physically changed me, but that was the case when the end credits of Nobuhiko Obayashi’s most famous work rolled. As far as I can tell, Hausu is the only work by Obayashi made easily available outside of Japan. (Actually, 1966’s Emotion is an extra on the Criterion disc, so I guess that counts too.) This became a problem when I’d finished watching Hausu, because, damn it, I wanted more! Happily, I’ve been able to track down more than a few of Obayashi’s unique films and one of the most enjoyable thus far has been School in the Crosshairs.

It was love at first sight. Oh Hausu (1977) – what a film! Not often do I feel that a film has physically changed me, but that was the case when the end credits of Nobuhiko Obayashi’s most famous work rolled. As far as I can tell, Hausu is the only work by Obayashi made easily available outside of Japan. (Actually, 1966’s Emotion is an extra on the Criterion disc, so I guess that counts too.) This became a problem when I’d finished watching Hausu, because, damn it, I wanted more! Happily, I’ve been able to track down more than a few of Obayashi’s unique films and one of the most enjoyable thus far has been School in the Crosshairs.

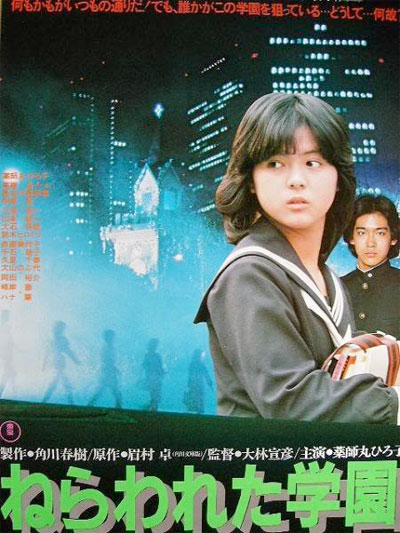

SCHOOL IN THE CROSSHAIRS

original title: ねらわれた学園 (Nerawareta gakuen)

aka: The Aimed School

Japan, 1981, Nobuhiko Obayashi

Our heroine

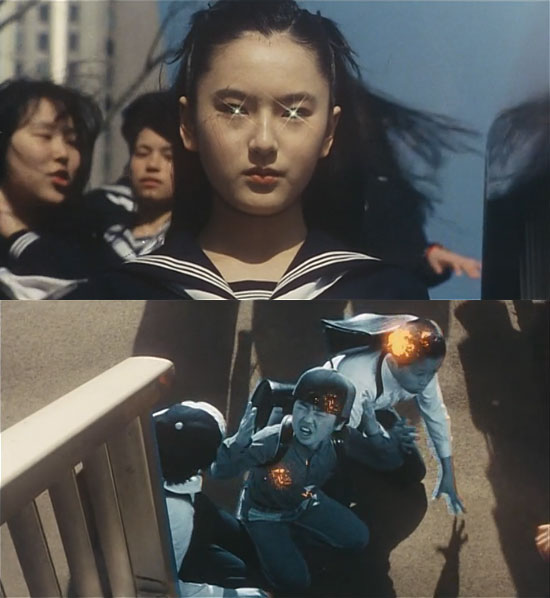

A demonic alien encourages Yuka to use her powers

Uniformed students enforce the school’s new strict rules

In some ways a prototype to Obayashi’s more well known film, The Little Girl Who Conquered Time (1983), School in the Crosshairs is an Obayashi film from its opening frames. The film’s wonderful title sequences introduces Yuka through text, saturated animation and absurd video effects. This overwhelmingly bright opening is an excellent taste of things to come as we enter Obayashi’s unique world. Like the bulk of his work, School in the Crosshairs is entirely original in its execution. Obayashi creates a world that is sometimes subtlety surreal and, at other times, unabashedly insane. Obayashi doesn’t seem to have the ability to keep any moment grounded in reality, and, for all his strangely matted backgrounds and timelessly odd animation, I thank him for it. While School in the Crosshairs is not quite the visual assault of Hausu, the film’s final sequence come pretty close.

While its style is wild and its story is fantastical, School in the Crosshairs delivers a fairly grounded and easy to understand story with likeable heroes and even better villains. Hiroko Yakushimaru makes for an excellent lead, easily rising above what could have been a bland character. Despite her almost total lack of flaws, Yuka remains engaging. The cold and imposing Masami Hasegawa makes a perfect rival for Yuka and an excellent antagonist for the narrative. Tôru Minegishi also proves that he is more than a silly costume and, in his demonic alien role, is a dominating presence. But my favourite cast member and character would have to be Arikawa, played by Macoto Tezuka. Akirkawa is the classroom’s stereotypical nerd and Tezuka is clearly having a blast as he sniggers and snorts his way through the film.

Takamizawa uses her powers to take care of some perverted kids

Tôru Minegishi plays the film’s primary villain

Akirkawa, a fantastically over the top nerd

Obayashi has the uncanny habit of ending his movies perfectly, and School in the Crosshairs is no exception. After a wonderfully bizarre climax, Obayashi takes the time to calmly wrap things up. While the film’s final moments aren’t quite as effective as The Little Girl Who Conquered Time (which is a superior film all round), it still left me incredibly satisfied. A film by Obayashi is always an oddity. Despite their locations and cast, his films feel like they were made in another universe rather than Japan. Somehow they are both very entirely Japanese and entirely not – either way, a film by Nobuhiko Obayashi is entirely Nobuhiko Obayashi.

1 comment

School in the Crosshairs (dir. Nobuhiko Obayashi, 1981) | 4:3 says:

Oct 25, 2016

[…] reading on this film is this great piece by Dave Jackson over at Mondo […]