Michele Soavi is a familiar face to those that enjoy their horror with a European flavour. While he is generally discussed in terms of behind the scenes efforts, Soavi can be seen in small but memorable roles in, to name only a few, Fulci’s City of the Living Dead (1980), Lamberto Bava’s Demons (1985) and Argento’s Opera (1987). Soavi’s career in cinema began with a small acting gig in a film called Bambule (1979). Marco Modugno – Bambule‘s director – took a liking to the young Soavi and offered him the role of an assistant director. This was the start of an exciting career as an assistant director. Soavi has worked for many big names in Italian cinema and beyond from the trashy Joe D’Amato to Terry Gilliam. But most significant was Soavi’s role as Dario Argento’s protege. Working as a second assistant director, assistant director and second unit director on Argento masterworks like Phenomena (1985) and Tenebre (1982), Soavi soaked up knowledge from the great Argento. By the time Soavi directed his first theatrical feature, the D’Amato produced Deliria (1987), his skills behind the camera had come to fruition. Argento – with help from Modugno, D’Amato and Fulci – had planted the seed, growing a brilliant Italian master of the genre that would arguably outdo his teacher. Soavi would go on to direct a trio of stunning horror films from 1989 to 1993 – The Church (1989), The Sect (1991) and, his finest, Dellamorte Dellamore (1994). Tragically, the next four years saw Soavi removed from cinema in what would have surely been his golden age. Soavi left cinema after making Dellamorte Dellamore to care for his sickly son. Soavi returned to directing in 1999 with the two-part telemovie Ultimo 2 – La sfida. The films Soavi would make post-1999 seem to generate little fanfare, but with productions like Arrivederci amore, ciao, we can see that the Michele Soavi of Dellamorte Dellamore is alive and well.

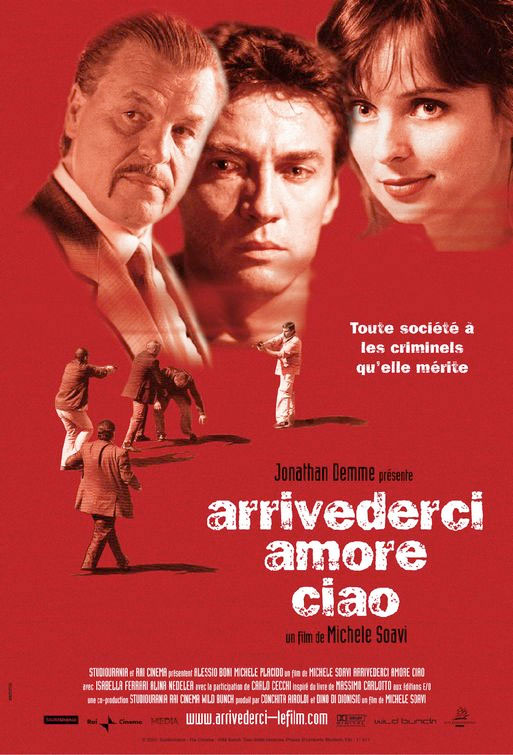

ARRIVEDERCI AMORE, CIAO

Italy, 2006, Michele Soavi

aka: The Goodbye Kiss

(US title)

, Goodbye My Love, Goodbye

(festival title)

For those that know Soavi for his dreamy horror films filled strange shots captured in wide angled lenses, Arrivederci amore, ciao is quite a shocking turn. When Soavi returned to cinema, he moved away from horror. He directed films – the majority in the crime genre – containing a realism previously unseen in his canon. Whether this was because of horror’s decline in popularity in the late 90s and early 2000s or a genuine choice on Soavi’s behalf, I’m not sure. But, even with this sharp change in story and genre, you can still find Soavi’s signature in Arrivederci amore, ciao and you don’t have to look that hard. Because I hate writing plot outlines, here is the plot summary on IMDB from Guy Bellinger:

Giorgio Pellegrini, a former left-wing activist turned terrorist has fled to Central America and fought with a guerrilla movement. Fifteen years later he is fed up with living in the jungle and decides to return to Italy. What he wants is to lead a comfortable bourgeois life in his native country. Thanks to Anedda, a corrupt police inspector, and after giving away former comrades, he obtains a reduced jail sentence. Once released from prison he obsessively pursues his dream of becoming a “respectable” citizen, even if the way to it is paved with larceny, pimping, drug-dealing, rape, heist and murder.

Guns and grit... something different for Soavi

The most striking element of Arrivederci amore, ciao‘s script – in which Soavi has a credit amongst many other names – is its leading character Giorgio. Giorgio – played by Alessio Boni – is a reprehensible character. He starts the film as a scumbag – with his superficial leftist leanings – and, rather than being redeemed, his morality continues to spiral downwards hitting despicable lows in the film’s final act. The script is composed of moments from Giorgio’s life as he destroys everything around him in an impossible attempt to achieve his goal of respectability. The corrupt police inspector Anedda (Michele Placido) is the connecting thread through the scenes; he is the character that continually appears, unwanted, in Giorgio’s life and aides him in his destruction. In its opening half, Arrivederci amore, ciao is fairly unpredictable in where it is heading. It sneakily appears to be a classic morality play where our lead will learn a lesson, but once its true direction becomes clear the film takes on a new layer of darkness. Unlike Soavi’s earlier works, there is no humour to be found in Arrivederci amore, ciao – and that works in its favour.

Giorgio: scum from the start

Soavi’s presence may not be evident in the film’s story and characters – as engaging as they may be – but his influence can certainly be seen in the film’s stylistic elements. Unlike his mentor, Argento – who seems to have forgotten how to make a film look great (or he’s just stopped caring), Soavi has remembered all his tricks. However, rather than his previous visual relentlessness, the Soavi of the 2000s does an excellent job of balancing his new found focus of realism with the stylistic flair of his past. Arrivederci amore, ciao is separated from your average modern crime thriller with its use of POV shots (shot in distorted wide lenses, of course), long sweeping takes and other complicated camera moves. The film’s finale is a collage of Soavi-isms, but I’ll avoid ruining any plot points by discussing it. Other than its ending, the beautifully staged strip club scenes are ripe with aesthetic flair. Using the setting to its advantage, Soavi adds lavish costumes, absurd lighting, creative transitions and his signature flowing camerawork to create fairly breathtaking – albeit low budget – sequences. These scenes utilise his skills in presenting the surreal while remaining grounded in realism. Below is the club’s first appearance (which includes a strange soundtrack of British band Fine Young Cannibals):

Arrivederci amore, ciao has some shocking moments – particularly towards the conclusion – but I’d be hard-pressed to place it in the exploitation genre. Even Soavi’s early work is not particularly graphic or exploitative. However, his role in Italian horror is incredibly important. The large gap in his filmography weaned attention away from his work, but his fans that are yet to check out his films post-Dellamorte Dellamore will be pleased to find out that he is still working. Not only that, Arrivederci amore, ciao shows that his time away has not affected his abilities as a filmmaker. I highly recommend that lovers of Italian genre films seek out Soavi’s newer efforts (Arrivederci amore, ciao, while hardly recent at 2006, I still consider a “newer effort”). The man who should have been Italian horror’s saving grace throughout the 1990s deserves to have his films seen and supported. (Imagine how different Italian horror in the 90s would have been with Soavi there.) Arrivederci amore, ciao is a great place to start when you’re desperate for more after finishing with his frustratingly minuscule 80s and 90s output.

A decade past his peak, Soavi still has it