Tetsuji Takechi – no stranger to Mondo Exploito – was an essential figure of 1960s pink cinema. With Daydream (1964), he made the first mainstream pinku eiga, but with Black Snow, he really ruffled feathers. In 1965, the release of Black Snow saw Takechi arrested on obscenity charges. His arrest led to a backlash from Japanese intellectuals and fellow filmmakers who fought on Takechi’s behalf. He won his trial and ushered in an influx of pink cinema. Yet for all its importance in pink cinema history and censorship, Black Snow – and Tetsuji Takechi for that matter – is largely forgotten.

Tetsuji Takechi – no stranger to Mondo Exploito – was an essential figure of 1960s pink cinema. With Daydream (1964), he made the first mainstream pinku eiga, but with Black Snow, he really ruffled feathers. In 1965, the release of Black Snow saw Takechi arrested on obscenity charges. His arrest led to a backlash from Japanese intellectuals and fellow filmmakers who fought on Takechi’s behalf. He won his trial and ushered in an influx of pink cinema. Yet for all its importance in pink cinema history and censorship, Black Snow – and Tetsuji Takechi for that matter – is largely forgotten.

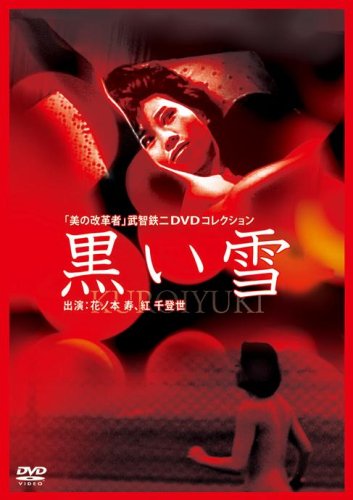

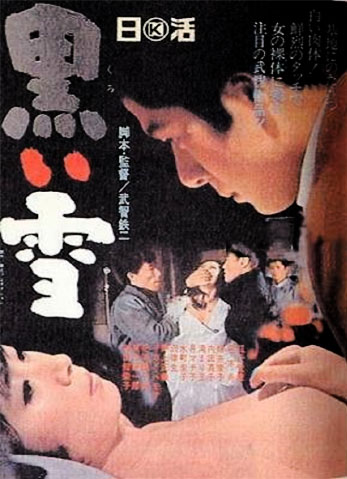

BLACK SNOW

original title: 黒い雪 (Kuroi yuki)

Japan, 1965, Tetsuji Takechi

Jiro finds out that his aunt is holding onto a whopping twenty grand (dollars, not yen) for an American officer. He kills a drunken American G.I. with a knife, steals his gun, and, working with two more experienced local thugs, sets to work stealing the money. Meanwhile, he begins a relationship with an innocent young woman, the sickly daughter of a taxi driver – a relationship which he reluctantly destroys by selling her virginity to one of his repulsive criminal friends.

Jiro is about as grim as protagonists come. He commits reprehensible acts – pimping an unknowing girl, murder, incestuous sex – and he is filled with fury, his existence suffocated by the American forces. Like many of the male leads of 1960s pink cinema, Kotobuki Hananomoto gives a performance dripping with blank-faced nihilism, though his quiet presence is made unique by a showing of compassion and regret.

As you may have guessed, Black Snow was not banned for its sexual content, even if that was the excuse given. Still, Takechi flaunts sexuality in the faces of the censors from the opening moments. Suggestive shots of a woman’s hairy armpit give the middle finger to the government’s repression of genitalia and pubic hair. In a lengthy scene, a woman runs naked against the military backdrop of the Yokota airbase. Jiro’s mother brings her quivering, sobbing son to her naked breasts in a creepy moment of nurturing and comfort. While there’s nudity and sexual content, Black Snow is hardly erotic and barely a pink film.

Its political content brought the wrath of the censors and the United States. As stated by Takechi, “I admit there are many nude scenes in the film, but they are psychological nude scenes symbolising the defenselessness of the Japanese people in the face of the American invasion.” His point is loud and clear throughout the film. Perhaps too loud at times. Black Snow is very heavy-handed, nationalist and even somewhat racist.

Stylistically, Black Snow is made with a raw playfulness. There’s a shaky charm to the cinematography. Shots linger with wobbly zooms. Sometimes the focus is off, and Takechi’s techniques don’t always work. In particular, Black Snow stumbles in its depictions of violence. The two scenes involving a murder are edited awkwardly, almost becoming unintentionally funny. But I think Takechi, with his ear-piercing soundscape and black and white photography, successfully builds a bleak world – a world that almost seems unique to the pinku eiga of the 60s.

Black Snow is absolutely a must-see of pink cinema. I don’t think anyone would accuse it of being a cinematic masterpiece, but its importance is undeniable. And while it’s not a brilliant film, it’s not a bad one either. Whether you agree with its politics or not, Black Snow is, nonetheless, fascinating.

Availability:

Black Snow was released on DVD in Japan in 2007. It’s now out of print and absurdly expensive. The print is excellent, but there’s no subtitles. There are, however, very good fansubs floating about on the internet.