With Crazy Thunder Road, Sōgo Ishii, Japan’s foremost director of punk cinema, takes us to a dystopian world of bikers, right-wing militia, explosions, children shooting up heroine, and relentless Japanese punk music. Ishii was only twenty when he shot this film. It was, in fact, his graduating project at film school. Toei bought the rights to it and blew up its 16mm print to 35mm. Boy am I glad they saw its potential.

With Crazy Thunder Road, Sōgo Ishii, Japan’s foremost director of punk cinema, takes us to a dystopian world of bikers, right-wing militia, explosions, children shooting up heroine, and relentless Japanese punk music. Ishii was only twenty when he shot this film. It was, in fact, his graduating project at film school. Toei bought the rights to it and blew up its 16mm print to 35mm. Boy am I glad they saw its potential.

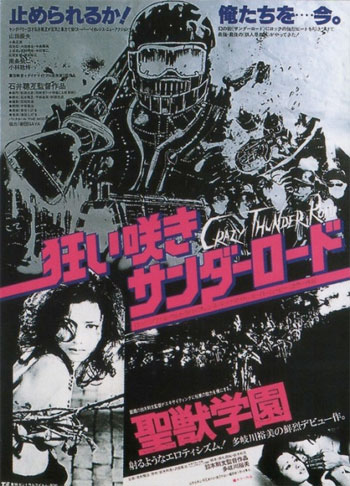

CRAZY THUNDER ROAD

original title: 狂い咲きサンダーロード (Kuruizaki Sandā Rōdo)

Japan, 1980, Sōgo Ishii

The crumbling borderline-apocalyptic city (based on the background graffiti, it’s set in the late 80s) is full of a variety of biker gangs, and none of them are fans of Jin and his pals. They unionise, joining forces to take out the Mabiroshi gang. Jin’s refusal to back down leads to the death of Yukio (Masamitsu Ohike), a metallic jawed Mabiroshi member.

In response to his friend’s death, Jin’s cohorts feel they need protection from the rival gangs and seek help from Takeshi (Nenji Kobayashi), the “old man” (he’s probably only in his thirties) who founded the Mabiroshi gang. Takeshi is putting together a fascist militia transforming wayward punks into protectors of the nation. Jin, understandably, is not pleased with this development. Cue chainsaws, dynamite and big guns.

Crazy Thunder Road is about as exciting as it sounds. What begins as a kind of Japanese version of The Warriors becomes a far different beast as it moves forward. Ishii directs this film with the same fire found in the early films of directors like Shinya Tsukamoto and Sam Raimi. The editing and camerawork is frantic, pounding from shot to shot, barely taking a breath between scenes. Crazy Thunder Road is pure punk energy with an authenticity that could never be replicated on a big budget.

Tatsuo Yamada is incredible as Jin. At first he appears to be the film’s antagonist. And he is in many ways. He antagonises everyone unlucky enough to be in his way, chewing, spitting and growling tough guy rhetoric. But as his gang sells out and become right-wing scum, his fury is justifiable, and I challenge anyone not to be cheering on his bloody vengeance.

In tune with Ishii’s direction and Yamada’s performance, Crazy Thunder Road‘s soundscape is a constant and loud. I really badly want the film’s soundtrack. I have no idea who any of the Clash-inspired Japanese punk artists are, but practically every track had me brimming with excitement. (Seriously: if anyone knows where I can find this soundtrack, please let me know.)

I don’t want to give too much away, but Crazy Thunder Road‘s final moments are spectacular. It ends perfectly in a way that is conventional in some sense with a character riding off into the sunset, but also unexpected in its tangential update on Ken’s post-biker life. It’s the kind of ending that could only come from a bold and ballsy young filmmaker. And only a bold and ballsy young filmmaker could include a shot of a child shooting up junk.

While Tetsuo, the Iron Man and Akira brought Japanese cinema back into the limelight and came to define a unique style of filmmaking, Ishii, with this, Panic High School (1978) and Burst City (1982), was their precursor, a decade earlier. Though the end product was distributed by Toei, Ishii demonstrated what film in Japan could be without a studio’s backing. His influence on modern Japanese cinema can still be felt, though very few recent offerings can come close to capturing his explosive energy.

Availability:

Rather shockingly, Crazy Thunder Road doesn’t appear to have been released on Western shores as of yet. It’s available in Japan (without subtitles) in a few different editions.