The Guinea Pig series spawned some of the most controversial films to be released in Japan. And, without a doubt, they are the most infamous video releases of the late 80s and early 90s – both in the East and the West. Floating around on tattered bootlegs in the early 1990s, the second Guinea Pig installment, Flowers of Flesh and Blood, terrified college students, Charlie Sheen, the MPAA, the FBI and even hardened gore-hounds. Nothing could possibly imitate the horror caused by those hazy videotapes, so when the Guinea Pig collection was finally released on DVD, it was met with a universal sigh of disappointment. With the video and audio cleaned up, suddenly these nasties from Nippon weren’t evil incarnate anymore. Some reviewers even referred to the performances and sound effects (especially in Flowers of Flesh and Blood) as laughable. Horror fanboys bought the now out of print DVDs regardless, tossed them on their shelves to gather dust and begrudgingly returned to their never-ending search for the most offensive movie in the world.

The Guinea Pig series spawned some of the most controversial films to be released in Japan. And, without a doubt, they are the most infamous video releases of the late 80s and early 90s – both in the East and the West. Floating around on tattered bootlegs in the early 1990s, the second Guinea Pig installment, Flowers of Flesh and Blood, terrified college students, Charlie Sheen, the MPAA, the FBI and even hardened gore-hounds. Nothing could possibly imitate the horror caused by those hazy videotapes, so when the Guinea Pig collection was finally released on DVD, it was met with a universal sigh of disappointment. With the video and audio cleaned up, suddenly these nasties from Nippon weren’t evil incarnate anymore. Some reviewers even referred to the performances and sound effects (especially in Flowers of Flesh and Blood) as laughable. Horror fanboys bought the now out of print DVDs regardless, tossed them on their shelves to gather dust and begrudgingly returned to their never-ending search for the most offensive movie in the world.

I first saw the Guinea Pig films in 2002 at the age of sixteen, and, while reviewers were disappointed by their lack of shocks, my impressionable mind felt violated by the big three: The Devil’s Experiment, Flowers of Flesh and Blood and Mermaid in a Manhole. Strangely enough, two of these entries were directed by Hideshi Hino, the comic writer-artist who had traumatised me as a child when I read my older brother’s copy of Panorama of Hell. Hideshi Hino remains an unhealthy idol of mine. But it was the original Guinea Pig film – not directed by Hino – that I watched first. I distinctly remember watching The Devil’s Experiment with my friends Tim (Tim and I were on a mission at the time to find the most awful and disturbing films we could find – just like any other horror-loving teen) and Richard. Richard stormed out almost instantly, disgusted, but Tim and I (stupidly?) continued to the end. When it was finished, Tim used the words “total nihilism” to describe it, which I still think would make the perfect tagline for the Guinea Pig series (and a lot of other Japanese films and videos, hence this regular article’s title).

The Guinea Pig films are not the sort of thing I like to watch regularly… I don’t think they’re the sort of thing that anyone would want to watch regularly – unless you’re the Otaku murderer or you’re attempting to learn special effects. In the past ten years, since ordering the DVDs, I’ve watched The Devil’s Experiment and Mermaid in a Manhole only once, and Flowers of Flesh and Blood maybe twice. Considering it is somewhat of a ten year anniversary for Guinea Pig – in terms of being widely available to the public – I thought it was time to watch them again and see what my reaction is as an adult. The response to their original DVD release was widely negative and their infamy was thoroughly diminished. But was that a knee-jerk response? Are they as horrible as they were when circulating on video in the early 1990s? Or are they overrated garbage? I will only be discussing The Devil’s Experiment, Flowers of Flesh and Blood and Mermaid in a Manhole. (The other Guinea Pig films aren’t bad at all, but they are more or less comedies.) They are in the order of how I re-watched them, rather than in order of release.

MERMAID IN A MANHOLE

original title: Ginî piggu: Manhôru no naka no ningyo

video release: 1988, director: Hideshi Hino

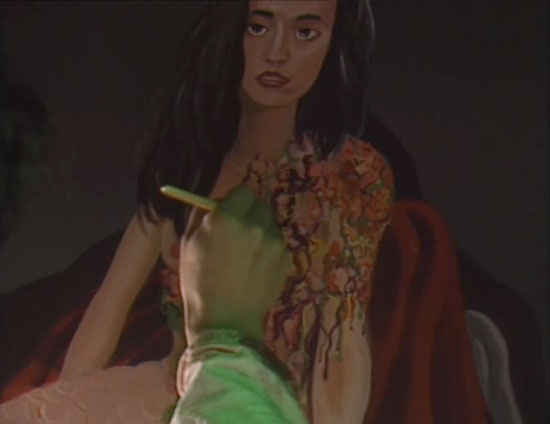

Mermaid in a Manhole does not carry the reputation of Flowers of Flesh and Blood or even The Devil’s Experiment. The fourth Guinea Pig film to be released, Hideshi Hino returned to the directorial reigns and adapted one of his manga stories. I’ve never read the original manga – I searched everywhere in Tokyo for the magazine it was original printed in – but thematically the film is very in tune with Hino’s most well known works. An artist (Shigeru Saiki) – a character that reminded me of the protagonist of Panorama of Hell – visits the sewers in order to find the inspiration for his paintings. Amongst the garbage, sludge and corpses of infants, he finds a mermaid (Mari Somei). He realises that he met this mermaid in his childhood. The sewers have infected her, leaving nasty pustular wounds over her body. The artist takes her home to look after her, but instead the dying mermaid requests that he paints her… using the colourful pus from her wounds.

Mermaid in a Manhole does not carry the reputation of Flowers of Flesh and Blood or even The Devil’s Experiment. The fourth Guinea Pig film to be released, Hideshi Hino returned to the directorial reigns and adapted one of his manga stories. I’ve never read the original manga – I searched everywhere in Tokyo for the magazine it was original printed in – but thematically the film is very in tune with Hino’s most well known works. An artist (Shigeru Saiki) – a character that reminded me of the protagonist of Panorama of Hell – visits the sewers in order to find the inspiration for his paintings. Amongst the garbage, sludge and corpses of infants, he finds a mermaid (Mari Somei). He realises that he met this mermaid in his childhood. The sewers have infected her, leaving nasty pustular wounds over her body. The artist takes her home to look after her, but instead the dying mermaid requests that he paints her… using the colourful pus from her wounds.

What struck me watching this after ten years – and having read many more of Hino’s comics – is how instantly recognisable Hino’s stamp is both in terms of its story and its visuals. This may be obvious considering that he directed the film and it is based on his work, but his creative control over the project is clear and overwhelming. Mermaid in a Manhole made quite an impact on me as a teenager. Watching it now, at first I thought its impact had been lessened whilst the film chugged through its first quarter.  Saiki is embarrassingly ridiculous as the artist. He plays the role with bugged eyes and shouted lines giving the film an instant cartoonish vibe. Hino also shoots the film with colourful lighting straight out of an Argento film – albeit not as technically apt – and dollops on a whole lot of cheesy slow motion to go with the fairly unremarkable camerawork. The hyperactive nature of Mermaid in a Manhole was something I’d completely forgotten. I was starting to think that I’d imagined the sick feeling this film gave me as a teen.

Saiki is embarrassingly ridiculous as the artist. He plays the role with bugged eyes and shouted lines giving the film an instant cartoonish vibe. Hino also shoots the film with colourful lighting straight out of an Argento film – albeit not as technically apt – and dollops on a whole lot of cheesy slow motion to go with the fairly unremarkable camerawork. The hyperactive nature of Mermaid in a Manhole was something I’d completely forgotten. I was starting to think that I’d imagined the sick feeling this film gave me as a teen.

Then the foulness slowly trickled onto the screen and into my living room. Mermaid in a Manhole may be somewhat goofy in its performances, but, once the pus and worms started flowing, my skin began to crawl as it had all those years ago when I first watched it on my old tube television. Mermaid in a Manhole does not build in a narrative sense, rather it builds in terms of its sickness. As the mermaid becomes more disfigured and repulsive, the film demands a growing physical reaction from its viewer. Mondo Exploito scribe Pierre describes the feeling he gets from Mermaid in a Manhole as tantamount to car sickness. For me, the nausea is there, but more so I find myself scratching my skin frantically as the mermaid’s infections explode with pus. Worst of all is a scene involving worms and centipedes (which you can watch below, but out of context it probably doesn’t work). As the slimy parasites burst their way through the mermaid’s wounds, I found myself close to turning from the screen. In all its cheapness and trashiness, Mermaid in a Manhole remains as effective as ever. I’m kind of pleased that ten years worth of exploitation and horror hasn’t left me completely jaded.

Mermaid in a Manhole – Worms and Wounds by MondoExploito

Bonus tidbit: My girlfriend pointed out while we were watching this that Masami Hisamoto has a weird appearance in the film playing a nosy neighbour. Apparently Hisamoto is a bit of a television star in Japan appearing on talk shows with her distinctive buckteeth and mole. I hear she’s also a bit of an internet meme. What the hell was she doing in Guinea Pig?

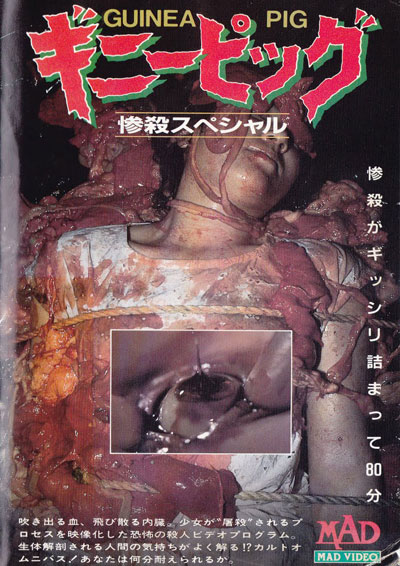

FLOWERS OF FLESH AND BLOOD

original title: Ginî piggu 2: Chiniku no hana

video release: 1985, director: Hideshi Hino

The second Guinea Pig installment, Flowers of Flesh and Blood, is a film bathed in infamy and legend. By far the biggest shit-stirrer of the series, Flowers of Flesh and Blood is the primary cause of the Western world’s obsession with the Guinea Pig films. Foremost, it was Charlie Sheen’s coke-hazed mind that brought the film to attention of the American authorities. Having seen it at a party, Sheen thought it was genuine snuff and insanely contacted the MPAA. The MPAA called the FBI only to find out that the Guinea Pig films were already under investigation by both the FBI and Japanese authorities. The filmmakers had to prove their effects were fake in court, which happily lead to an excellent behind the scenes featurette provided on the DVD. To put yourself in Sheen’s head-space (sorry), the version he saw of Flowers of Flesh and Blood was not the crisp image we see on the DVD. Sheen would have watched a haggard bootleg. The DVD by Unearthed Films brilliantly supplies an  Easter egg of an old dubbed source of the film. Watching the classic incarnation of Flowers of Flesh and Blood is pretty creepy. Flowers of Flesh and Blood received further infamy when the Otaku murderer – Japanese serial killer Tsutomu Miyazaki – was misreported as having reenacted scenes from the film in his murders. Miyazaki actually had only Mermaid in a Manhole in his extensive collection, but Flowers of Flesh and Blood remained the focus in much of the reporting.

Easter egg of an old dubbed source of the film. Watching the classic incarnation of Flowers of Flesh and Blood is pretty creepy. Flowers of Flesh and Blood received further infamy when the Otaku murderer – Japanese serial killer Tsutomu Miyazaki – was misreported as having reenacted scenes from the film in his murders. Miyazaki actually had only Mermaid in a Manhole in his extensive collection, but Flowers of Flesh and Blood remained the focus in much of the reporting.

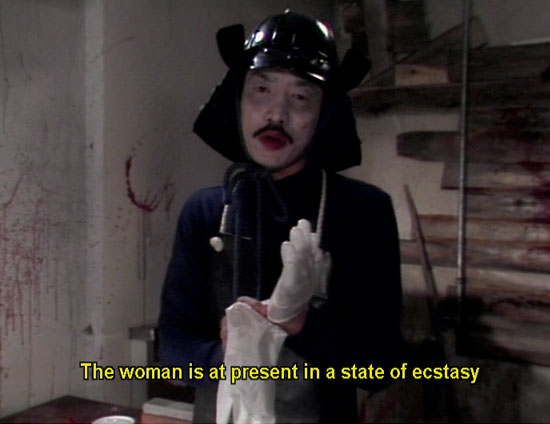

I hate to sound like a typically cynical horror viewer, but Flowers of Flesh and Blood‘s history is far more interesting than the film itself. Originally when I watched this, I felt a little guilty by the film’s finale, mainly because it was so violent, but this feeling dissipated pretty quickly. I thought that giving ten years between viewings would allow me to see Flowers of Flesh and Blood in a new light and possibly even have it affect me as it did Charlie Sheen and the FBI. But no, my reaction to it was practically identical to my original viewing – minus the guilt. Flowers of Flesh and Blood is essentially plot-free. A man (Hiroshi Tamura) kidnaps a woman (Kirara Yûgao). He dresses up as a samurai and slowly dismembers her and rambles about flowers blooming. Like Mermaid in a Manhole, Flowers of Flesh and Blood has a surprising goofiness to it. The dialogue is typically Hino, meaning it is wordy and not particularly realistic. Tamura is outrageous in the lead with his terribly fake missing teeth, pasty make-up and silly samurai get up. His monologues, delivered to camera, do nothing except take away any shock value the film might have had without them. The sound effects – a lot has been said about this – are awful. They are loud and abrasive sounding like a shitty sound effects CD from a bargain bin. They lessen the impact of the practical effects majorly. Early on in the film, Tamura holds up a chicken and demonstrates to his captive what her fate will be – this is not simply shown metaphorically, he actually says this. He chops off the chicken head, the body falls to the ground in post-slow-mo making a ridiculous sound as it hits the ground. This scene is a good introduction to the silliness to come. The decapitation is quite comical due to how fake it looks – not that I’m encouraging the murder of animals for film – and its presence does the film no favours.

Flowers of Flesh and Blood – Goofy Chicken… by MondoExploito

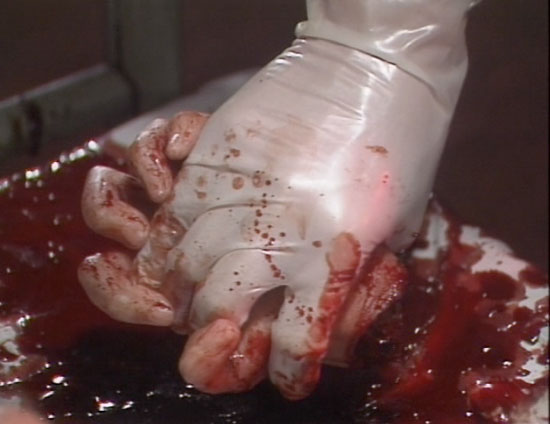

Flowers of Flesh and Blood may not be the shocker that it was made out to be all those years ago, but it is not a total waste of time. On the contrary, its exaggerated nature makes it an easier film to watch than both Mermaid in a Manhole and The Devil’s Experiment. It’s funny that the most infamous of the Guinea Pig series is one of the more entertaining entries with all its buckets of blood and theatrical dialogue. The effects are also total technical perfection. Severed hands grasp at the samurai murderer post removal, eyes are hideously scooped out of sockets and legs are realistically hacked off. The effects are impressive indeed. But rather than being offensive, they take on a dreamlike quality. Flowers of Flesh and Blood feels far removed from realism – making it all the more surprising that it was mistaken for a snuff film. With its wandering dialogue, strange camerawork and filtered lights, it often feels more like an experimental film – an experimental film with a lot of

(literal) guts. Revisiting Flowers of Flesh and Blood has been interesting, but only because my opinion of it has not budged an inch.

(literal) guts. Revisiting Flowers of Flesh and Blood has been interesting, but only because my opinion of it has not budged an inch.

Flowers of Flesh and Blood may not be the shocker that it was made out to be all those years ago, but it is not a total waste of time. On the contrary, its exaggerated nature makes it an easier film to watch than both Mermaid in a Manhole and The Devil’s Experiment. It’s funny that the most infamous of the Guinea Pig series is one of the more entertaining entries with all its buckets of blood and theatrical dialogue. The effects are also total technical perfection. Severed hands grasp at the samurai murderer post removal, eyes are hideously scooped out of sockets and legs are realistically hacked off. The effects are impressive indeed. But rather than being offensive, they take on a dreamlike quality. Flowers of Flesh and Blood feels far removed from realism – making it all the more surprising that it was mistaken for a snuff film. With its wandering dialogue, strange camerawork and filtered lights, it often feels more like an experimental film – an experimental film with a lot of (literal) guts. Revisiting Flowers of Flesh and Blood has been interesting, but only because my opinion of it has not budged an inch.

THE DEVIL’S EXPERIMENT

original title: Ginî piggu: Akuma no jikken

video release: 1985, director: Satoru Ogura

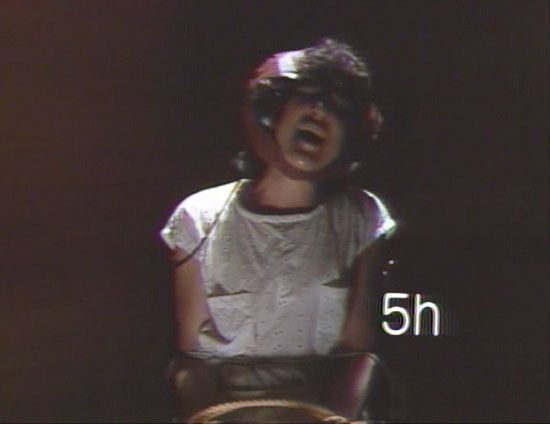

I re-watched The Devil’s Experiment last. Not because I was saving the best till last – if there is such a thing as “the best” when it comes to these films – but because I was genuinely uncomfortable about watching it again. The Devil’s Experiment upset me a lot the first and – up until today – only time I watched it. It managed to leave me depressed for quite some time after viewing it and forced me to ask myself how I could sit through such an awful movie. The Devil’s Experiment is even more stripped back than Flowers of Flesh and Blood. We open with text telling us of a video the producers/distributors – the voice of the textual narration is referred to only as “I” – have received a video of a woman being put through a series of tortures and then killed. It is some kind of experiment of human limitations, but in reality it is just plain barbaric cruelty. After the text – unlike Flowers of Flesh and Blood, which at least has some kind of set up, thin as it is – it throws to a flickering shot of a – possibly dead – woman hanging in a net from a tree. (This image haunted me as a youngling.) We then instantly cut/flashback to the tortures that preceded her death. The tortures are written in kanji and English at the bottom of the screen, with examples being “hit” and the concluding “needle.”

I re-watched The Devil’s Experiment last. Not because I was saving the best till last – if there is such a thing as “the best” when it comes to these films – but because I was genuinely uncomfortable about watching it again. The Devil’s Experiment upset me a lot the first and – up until today – only time I watched it. It managed to leave me depressed for quite some time after viewing it and forced me to ask myself how I could sit through such an awful movie. The Devil’s Experiment is even more stripped back than Flowers of Flesh and Blood. We open with text telling us of a video the producers/distributors – the voice of the textual narration is referred to only as “I” – have received a video of a woman being put through a series of tortures and then killed. It is some kind of experiment of human limitations, but in reality it is just plain barbaric cruelty. After the text – unlike Flowers of Flesh and Blood, which at least has some kind of set up, thin as it is – it throws to a flickering shot of a – possibly dead – woman hanging in a net from a tree. (This image haunted me as a youngling.) We then instantly cut/flashback to the tortures that preceded her death. The tortures are written in kanji and English at the bottom of the screen, with examples being “hit” and the concluding “needle.”

In this returned viewing of The Devil’s Experiment, I’m going to attempt to work out exactly what it is that I find so unsettling about this cheap and nasty video. A popular opinion of this entry – and its followup – is that the lack of any semblance of plot creates a less disturbing experience. In theory, that makes sense. If we can’t care about the characters, the film can’t affect us. But its complete annihilation of story, for me at least, lays the groundwork of the film’s effectiveness. With no plot and no background to the characters, we have a film that is pure violence and pure evil. The only aspect of structure in The Devil’s Experiment is that it becomes more hideous and brutal as it moves towards its horrible conclusion. Like a modern day porno, there is no substance. And instead of lovely fucking, there’s punching, kicking and cutting, which the camera salivates over. The pornographic atmosphere is further established through the video aesthetic. All of this plants the seed of an uncomfortable thought that The Devil’s Experiment is intended to titillate its viewers rather than disturb, which, of course, makes the film all the more disturbing. I don’t know if this was deliberate on the filmmakers behalf, but it certainly made me feel a little ill.

evil. The only aspect of structure in The Devil’s Experiment is that it becomes more hideous and brutal as it moves towards its horrible conclusion. Like a modern day porno, there is no substance. And instead of lovely fucking, there’s punching, kicking and cutting, which the camera salivates over. The pornographic atmosphere is further established through the video aesthetic. All of this plants the seed of an uncomfortable thought that The Devil’s Experiment is intended to titillate its viewers rather than disturb, which, of course, makes the film all the more disturbing. I don’t know if this was deliberate on the filmmakers behalf, but it certainly made me feel a little ill.

There are plenty of horror films that strive to capture the jarring unpleasantness of The Devil’s Experiment – often by taking advantage of the supposed realism that comes with shooting on a cheap video format. Rarely does this work, but The Devil’s Experiment manages to pull it off. I think I’ve managed to pinpoint the reasons – obvious as some may be. Flowers of Flesh and Blood is a display of gooey special effects, The Devil’s Experiment approaches its effects differently. Rather than having a barrage of nonstop dismemberment, The Devil’s Experiment begins with simple (and realistic) tortures. The woman is slapped and kicked, spun around in a chair and pinched with a wrench. When the practical gore effects finally come into play – in the film’s final ten minutes – their impact is strengthened by the memory of the previous, relatable and realistic tortures fresh in the viewer’s mind. It also help that the effects are underplayed and shockingly realistic, as seen in the clip below.

The Devil’s Experiment – Hand cutting scene by MondoExploito

What I find most unsettling about The Devil’s Experiment is the glee that the torturers take in their task. Their dialogue is brutal, amateurish and filled with bile. Between yelling “whore” at the woman, they’ll shout: “you have nothing to live for, do you?” The resignation of the woman and the relentlessness of her captors is where the nihilism truly comes into play. There is a particularly shattering scene where the woman is pelted with raw meat, over and over, as the antagonists laugh. Rather than appearing as aggressive misogyny, this scene felt more like a generalised “fuck you” to the entire human race. The film often pauses the video after something horribly violent has happened – it’s like it’s asking the audience: “what the fuck is wrong with you? Why are you watching this? The world is a piece of shit, isn’t it?” The aggressors of The Devil’s Experiment quiet their taunts for the film’s final scene of extreme violence. The film flashes over previous moments of brutality inter-cut with a needle being inserted into the woman’s eye. Lingering on the frame like it was a cum shot, the video pauses and returns to our opening image of a woman – most likely dead – spinning in a net. Pure nihilism.

While I wasn’t left quite as devastated this time round, The Devil’s Experiment‘s evil power is still undoubtedly present. It won’t affect every viewer – if you watch it passively, it’s merely a few scenes of violence, but active viewers will find themselves feeling like total dog shit by the time the image fades to black. The Devil’s Experiment is also a good point to wrap up this article (it’s way too long, sorry). Watching the three most infamous Guinea Pig films again, I’m stunned at how similar my response has been compared to my original viewings. In the ten years since they were first released on DVD, my tastes have moved on from purely wanting to shock myself – even though I do like a good punch in the balls every now and then. At the same time, I have grown fond of the aesthetics of Japanese home video. For some reason, Japan pulls off the shot on video look. It still looks cheap, but they treat the format with dignity and respect. The video aesthetic – when used properly – can be powerful. The Guinea Pig films are proof of this.

While I wasn’t left quite as devastated this time round, The Devil’s Experiment‘s evil power is still undoubtedly present. It won’t affect every viewer – if you watch it passively, it’s merely a few scenes of violence, but active viewers will find themselves feeling like total dog shit by the time the image fades to black. The Devil’s Experiment is also a good point to wrap up this article (it’s way too long, sorry). Watching the three most infamous Guinea Pig films again, I’m stunned at how similar my response has been compared to my original viewings. In the ten years since they were first released on DVD, my tastes have moved on from purely wanting to shock myself – even though I do like a good punch in the balls every now and then. At the same time, I have grown fond of the aesthetics of Japanese home video. For some reason, Japan pulls off the shot on video look. It still looks cheap, but they treat the format with dignity and respect. The video aesthetic – when used properly – can be powerful. The Guinea Pig films are proof of this.

As a closing thought, a character in Ryu Murakami’s In the Miso Soup says of people who watch horror movies: “They want to be stimulated, and they need to reassure themselves, because when a really scary movie is over, you’re reassured to see that you’re still alive and the world still exists as it did before. That’s the real reason we have horror films – they act as shock absorbers – and if they disappeared altogether it would mean losing one of the few ways we have to ease the anxiety of the imagination.” I don’t think this applies to all horror films in all its forms, but I think it’s a more positive way to view the Guinea Pig films. Not that I’m trying to justify their content (nor would I do the opposite by complaining about them from a moral standpoint), I only want to ease the terror set in from watching these three films in a row and end on somewhat of a positive note. Except… the character that I’m quoting is a serial killer…

1 comment

Naked Blood: Megyaku (1996) | MONDO EXPLOITO says:

Nov 22, 2012

[…] attention. Thankfully, Naked Blood is more than just a blood bath. Its synopsis may remind some of Flowers of Flesh and Blood (1985), but Naked Blood has little in common with a Guinea Pig film. (Even the gore has a surreal […]