Watching a film you know nothing about can be an interesting experience. More often than not the film will turn out to be average; a film that’s not offensively bad, nor particularly good. If you’re lucky, a film you know nothing about can completely blow you away. It’s a rare experience for me – perhaps only happening once or twice a year. Concrete was a film I knew practically nothing about until today. I’m not even sure how I came across it. I think I’d read something about it being a particularly unpleasant film, so I noted it down as a potential candidate for Nihon Nihilism. Concrete is certainly not an average film. But rather than blowing me away with high quality filmmaking (and I’m not saying it’s poorly made – it’s actually very good), it blew me away with its horrific content. Yes, Concrete was hard one to sit through.

Watching a film you know nothing about can be an interesting experience. More often than not the film will turn out to be average; a film that’s not offensively bad, nor particularly good. If you’re lucky, a film you know nothing about can completely blow you away. It’s a rare experience for me – perhaps only happening once or twice a year. Concrete was a film I knew practically nothing about until today. I’m not even sure how I came across it. I think I’d read something about it being a particularly unpleasant film, so I noted it down as a potential candidate for Nihon Nihilism. Concrete is certainly not an average film. But rather than blowing me away with high quality filmmaking (and I’m not saying it’s poorly made – it’s actually very good), it blew me away with its horrific content. Yes, Concrete was hard one to sit through.

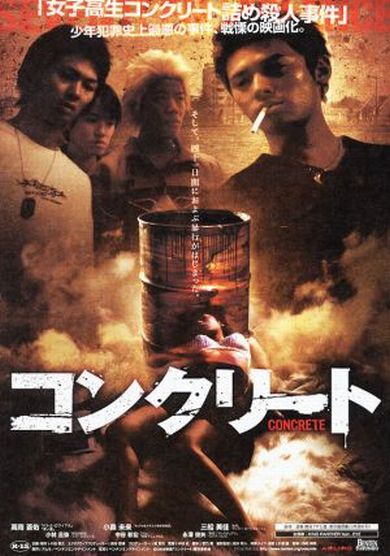

CONCRETE

original title: Konkurîto (コンクリート)

aka: Schoolgirl in Concrete

2004, Hiromu Nakamura

Tatsuo huffs glue

The hellish turning point in Concrete comes when Tatsuo is allowed to form his own gang. The gang is intended to be a quick money maker for Tatsuo’s yakuza boss; a gang of juvenile delinquents stealing handbags and tossing their earnings towards their superiors. Once Tatsuo becomes aware that he is being used, he begins to abuse his position of (minor) power. He starts by mugging and abusing high school girls, then the gang moves onto raping women. Soon, the gang appears to become purely dedicated to gang rape. The police seem unable to pin anything on Tatsuo and his thugs, despite being entirely aware of their guilt. Tatsuo, feeling bold from his invulnerability to prison, kidnaps a high school girl, Misaki (Miki Komori). After raping her, he takes her to his gang’s “office” – the office is simply the parental house of one of his underlings. Tatsuo and his gang repeatedly rape, torture and abuse Misaki over the course of at least a few months; the abuse continually getting worse. This makes up the last forty-five minutes of the film.

One of the many moments of humilation and abuse

As you can probably tell from the plot synopsis above, Concrete is bleak – as bleak as they come. And what makes it so much worse than your typical Japanese nihilism is that it is restrained. Concrete doesn’t go out for gore or shocks. The rape scenes are not shown in graphic detail and, while it is undeniably brutal, we are generally shown the aftermath of the violence rather than the act itself. This is extremely effective in creating an unbearably grim atmosphere. When Concrete actually shows violence, it is also subtle in its presentation. Rather than geysers of blood, we are given thudding punches and kicks that are effectively shown using inventive camerawork and editing rather than dodgy stunt work.

Mostly restrained, always horrible

Concrete also does an uncomfortably excellent job of creating a sense of realism. While the lack of effort from the police and the family residing in the gang’s “office” is frustrating, the authenticity of the leading characters more than make up for any leaps in logic. Tatsuo is a classic angry teenager, but his rage is certainly believable. While we aren’t really given clear-cut reasons for Tatsuo’s disconnection from the world around him, his actions are all too real and his character would be familiar to anyone who remembers their teen years. His gang is less defined, but, again, their juvenile aggressiveness is realistic. They are certainly not likable characters, and they are obviously the antagonists of the story, yet they are not painted as cut-and-dry villains. Their entrapment in the yakuza and subsequent descent into group-madness is surprisingly understandable, although it certainly does not justify their actions. The communal madness reminded me a lot of Jack Ketchum’s book, The Girl Next Door. The true impact of Concrete comes from Miki Komori’s soul-shattering performance as Misaki. Unlike mindless torture films (I’m looking at you, Guinea Pig), we get to know Misaki, and her horrendous treatment is upsetting to say the least. Komori gives a truly brave performance that really played with my emotions.

Miki Komori's performance shook me up

Concrete has a cheap look found in most shot-on-video productions from Japan, but director, Hiromu Nakamura, is impressively playful with his visuals at times. Not everything he attempts works, but there is a wonderful use of point-of-view shots and even a few excellent fantasy sequences that had me nodding with approval. On a purely structural level, Concrete is a thing of beauty. The film cuts perfectly between scenes, giving the audience just the right amount of information allowing viewers to fill in the gaps themselves. Hiromu Nakamura manages to incorporate flashbacks without them feeling forced and, even on the most basic level, he knows exactly how long a shot should linger for.

The strangely effective final scene of Concrete

Concrete left me thoroughly impressed but supremely depressed. I can highly recommend this for those that can handle this special brand of nihilism. That said, there’s no way I’ll be watching this again anytime soon! And to finish this article off, something that’s left me feeling even more bleak. I don’t have the internet at home at the moment, so I haven’t been able to do much in the way of research on this film. I’m posting this from my parents’ place after writing the text in Word. Before posting the article, I did a quick search for Concrete on Google to find that the film is based on a true story. What a rotten world we live in.